Alyssa Monks: Where the Self Blurs Into Being

Alyssa Monks seems most interested in the moment when the answer slips. Her paintings present bodies that look almost unbearably real, then dissolve into mist, streaks of color, coils of paint that behave like their own weather. The figure is there, close enough to touch. A pane of glass, a vinyl curtain, steam, water, foliage or oily light interrupts the view. We recognize a face or a gesture, then the surface takes over and we find ourselves looking at paint itself, thick and restless, recording every decision of the hand.

Self-portraiture, in this sense, is not a confession. It is an experiment. What happens to the self when it is filtered through water, grief, illness, isolation, or desire. What happens when it is filtered through oil and linen, through a brush that refuses to obey the photograph.

Monks began with what critics like to call hyperrealism. The early shower paintings, the bodies behind steamed glass, made it impossible not to marvel at the accuracy, the technical bravura. Yet even there something is already undoing that certainty. The spray of water, the fogged surface, the smears where a hand has wiped away condensation all begin to transform the image into a field of abstractions. We think we are looking at a woman in a private moment. We are also looking at patterns of light and matter, at a self that is already slipping into paint.

She has said that each brushstroke functions almost like a fossil, a trace of a gesture that cannot be repeated in exactly the same way. You can feel that fossilization when you stand in front of these works. The skin appears soft and vulnerable, yet the surface is rough, weathered, unpredictable. The painting refuses to become a smooth mirror. It insists on the distance between the image we expect and what the material world offers instead. Selfhood, here, is not a stable reflection. It is a series of failed attempts to match what we imagine with what actually appears.

At a certain point, the realism she had chased began to come apart. The break was not only aesthetic. The death of her mother shattered the old coordinates of control and safety. In the aftermath, Monks went into the landscape. Trees, leaves, flowers, thick undergrowth. She allowed the paint to behave less obediently, to spread, clot, drip, and blur. Precision gave way to curiosity. The world and the canvas both became less predictable. What she found there was not a retreat from the figure, but a new way of thinking about it.

When the body returns in later works, it does so inside this expanded climate. The figure is still particular. It is often her own body, her own face, her own history of loss and endurance. Yet that specificity is now surrounded and infiltrated by swirls of color, by water that clouds the view, by petals and branches that wrap themselves around the skin. The self lives inside an environment that is never neutral. It is tethered to weather, to illness, to chance.

The pandemic sharpened this awareness. Suddenly everyone was living behind glass. Everyone was counting droplets. Everyone was learning that a thin, invisible membrane could separate safety from danger, presence from absence. Monks returned to the shower motif with a different urgency. The bodies in the series It's All Under Control and This Is Not What You Wanted feel trapped in an aquarium of anxiety. We sense a woman pressing against the transparent barrier, yet she cannot quite emerge. The glass has become both shield and prison, both protection and accusation.

These paintings are self-portraits in the most literal way. She used her own likeness, her own mental states, as the subject. At the same time, they are portraits of dissociation and fear that don't belong to her alone. The face is often blurred, distorted by vapor and drops of water, broken into patches of color. That erasure matters. Once the features become less readable as "Alyssa", they become easier to inhabit. The self on the canvas ceases to be a private person and becomes a figure in which others can recognize their own helplessness, their own attempts to control the uncontrollable.

In her TED talk and interviews, Monks returns to the idea that our deepest suffering often comes from our attachment to control, to predictable outcomes, to a coherent story about who we are. These paintings push against that attachment. A realistic head dissolves into a storm of brushstrokes. A body floats in cloudy water that refuses to resolve into clear depth. A viewer approaches, hoping for clarity, and instead finds an image that both reveals and withholds. The self is present, yet always in the process of becoming something else.

This is where her work speaks to the philosophical questions at the heart of this issue. We are accustomed to thinking of a self-portrait as a statement of identity. This is me. This is what I look like. This is who I am. In the world of Alyssa Monks, such statements feel naive. The self in her paintings is contingent and unstable, shaped by losses and by the pressure to be a certain kind of woman under the gaze of others. It is also capable of slipping past those expectations, of becoming something fluid and strange.

There is no hidden essence to discover. There is only a history of descriptions that we inherit and then try to redescribe in our own terms. Monks gives this idea a visual form. She takes all the old vocabularies of representation, all the inherited conventions of figure painting and feminine beauty, and subjects them to new filters. Water, steam, vinyl, glass, flowers, oil on the surface of a bath become devices for redescription. They blur the obvious readings, invite misbehavior, prevent the viewer from settling into a single interpretation.

Her surfaces resist smooth illusion. They ask us to come close, to see the ridges of paint, the places where one decision was covered by another. The image becomes a record of thought in motion, a palimpsest. Doubt and revision are not hidden stages. They remain visible. In this way, the painting mirrors the process by which a person becomes themselves. We are all, in a sense, continuous revisions. The face the world sees is laid over an underpainting of older selves that never fully disappear.

There is also a quiet, insistent empathy in this work. The subjects, often women, appear in states of exposure that are not purely erotic, nor purely tragic. They seem caught between one emotional weather system and the next. The moment that interests Monks is the one "between feelings", when something has not yet fully arrived or has not yet entirely left. That in-between time is where vulnerability and strength coexist. The woman is naked and alone, yet there is a force in her restraint, a refusal to collapse into pure victimhood.

This tension between power and fragility is central to the politics of self-portraiture today. A female body rendered with such care risks being consumed as spectacle. Monks answers that risk by repeatedly placing a veil between viewer and subject. Water, glass, foliage, and blur function as shields. They also insist that intimacy must be negotiated. You are allowed to feel close to these figures, yet you are also reminded that they belong to themselves.

For this issue of The Pasticheur, which gathers artists and writers who turn the gaze inward in order to question what an I can be, Alyssa Monks occupies a crucial place. Her paintings remind us that the self we bring to the mirror is already layered, already porous, already marked by forces that exceed our control. They suggest that what we call "me" is often a thin membrane stretched over grief, fear, longing, and a stubborn desire to belong.

To look at her work is to stand outside a shower you cannot enter, watching someone who might be you breathe on the other side of the glass. The image is intimate and distant at once. It acknowledges the loneliness of a mind that feels trapped inside its own skin, and it offers a strange consolation. Whatever we are going through, someone else has felt it. Someone else has stood in that fogged enclosure and tried to make sense of the patterns on the surface.

In Alyssa Monks's hands, self-portraiture is not the revelation of a stable interior. It is the enactment of a process. A mind observes itself. A body is offered and withdrawn. A face comes into view, then dissolves into paint. What remains is not a final answer to the question Who is that?, but a field of possibilities where the self can be seen, misseen, and seen again.

Jorge R. G. Sagastume

Through Glass and Water

All My Desires, 2025

80 x 80 Inches, Oil on Linen

Glass, 2007

40 x 38 in., Oil on Linen

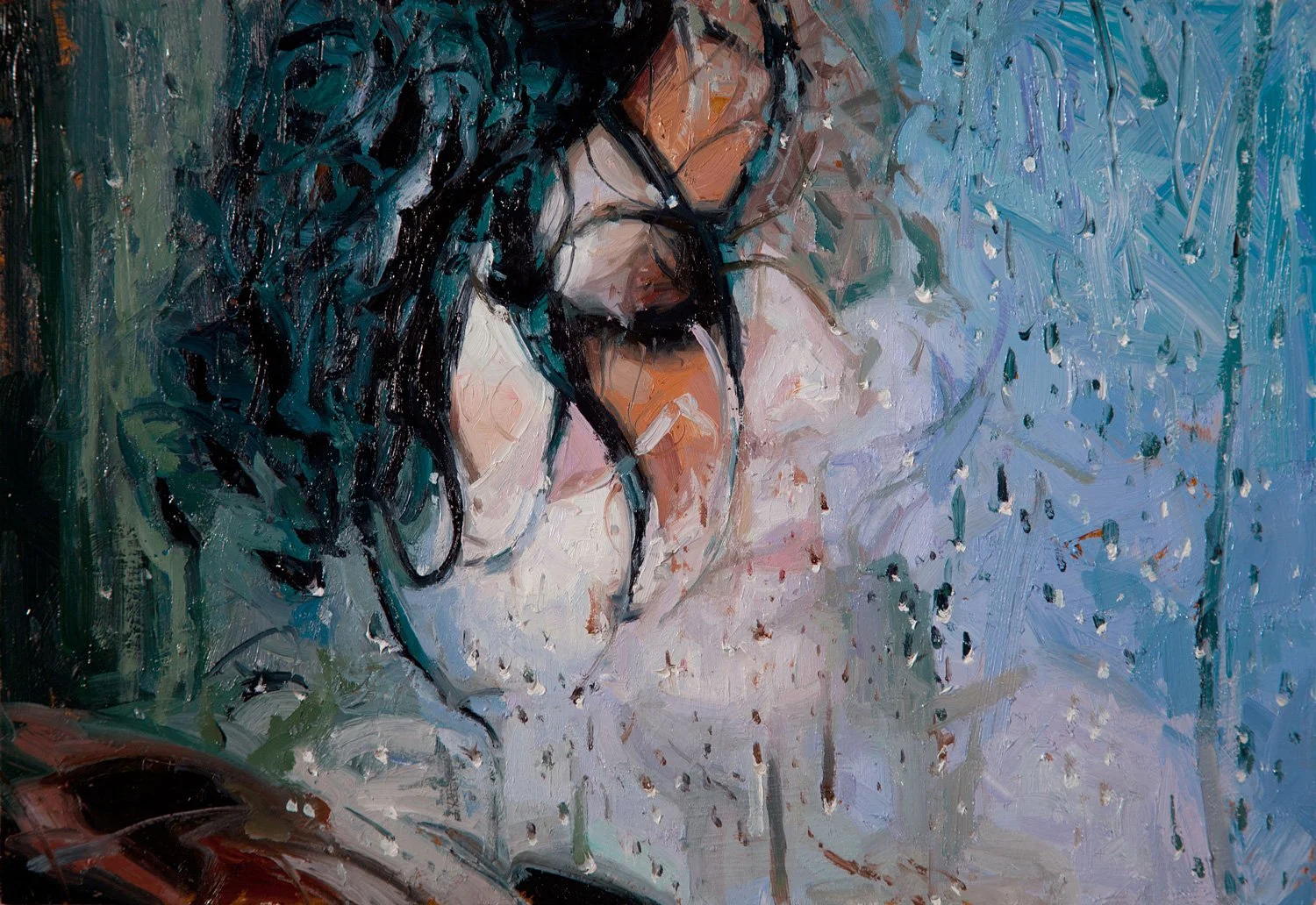

Cope, 2014

10 x 16 in., Oil on Panel

II. Into the Undergrowth

Emptying, 2014

10 x 16 in., Oil on Panel

Evolve, 2012

32 x 48 in., Oil on Linen

Penance, 2006

54 x 72 in., Oil on Linen

III. The Self Inside Weather

Goodbye, 2021

24 x 34 in., Oil on Linen

Disassociate, 2005

66 x 40 in., Oil on Linen

IV. Behind the Barrier

Hung Drawing, 2018

17 x 24 in., Charcoal on Paper

V. Where Paint Takes Over

Loss, 2014

48 x 72 in., Oil on Linen

It's All Under Control, 2021

62 x 90 in., Oil on Linen

© All Works by Alyssa Monks

Artists & Writers in This Issue

In alphabetical order by the first name