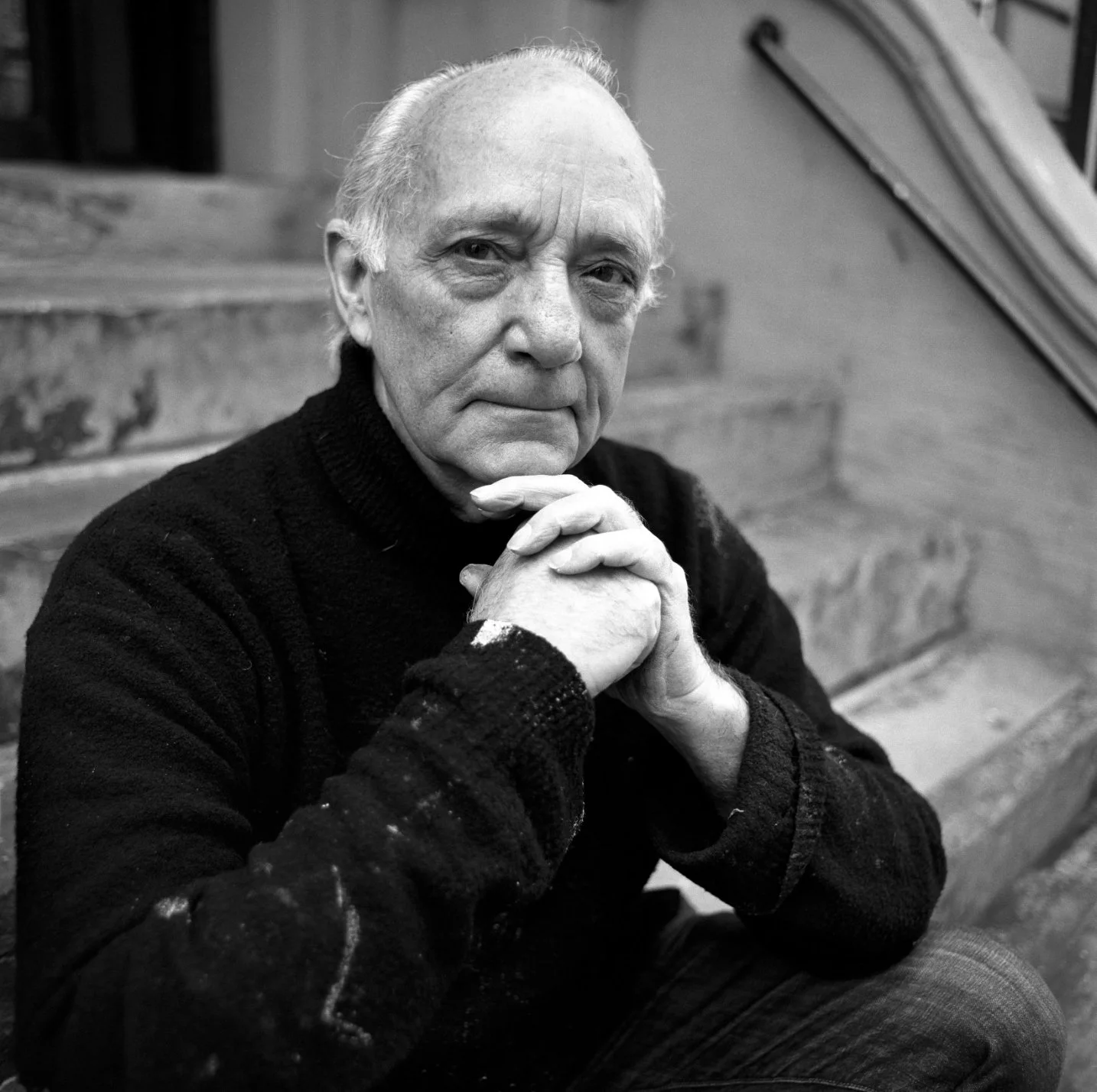

MARSHALL ARISMAN (1938 – 2022) was an American illustrator, painter, storyteller, and educator whose work wove together darkness, myth, and raw human emotion.

Born in Jamestown, New York, and raised on a dairy farm, Arisman developed a fascination early on with animals, ritual, and the psychological shadows beneath everyday life. After studying advertising art at Pratt Institute (class of 1960), he traveled in Europe on a grant, served in the U.S. military, and then began work as a graphic designer at General Motors, only to conclude that his true calling lay in art that spoke from within rather than serving a client’s script.

Arisman made his name in illustration, contributing striking images to prominent publications including The New York Times, Time, Playboy, Esquire, and Mother Jones. But in his hands, illustration and “fine art” were never distinct categories, both were arenas for narrative, for confronting violence, suffering, and spiritual paradox.

His paintings, and at times installations and multimedia works, delve into themes of predation and redemption, corporeal distortion and psychic rupture. One notable work, The Last Tribe (2009), blends painting, sculpture, and video to meditate on nuclear annihilation. And perhaps his most famous editorial piece was the Time magazine cover “The Curse of Violent Crime” (1981), a haunting image that elicited both disquiet and acclaim.

Arisman’s influence extends into pedagogy. In 1984, he founded and led the MFA program Illustration as Visual Essay at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City, envisioning illustration not as a craft but as a medium of storytelling. He remained a guiding presence in SVA’s community until his sudden death in 2022 from heart failure.

His works enter the collections of institutions such as the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and others; his exhibition Sacred Monkeys was the first solo show by an American artist in mainland China. Beyond visual media, Arisman also released Cobalt Blue (2008), an audio-narrative album tied to his artwork, and published books including Frozen Images and The Divine Elvis.

Arisman’s life and art resist clean categorization. He asked, provocatively: “Does that make sense?”, not as a question, but as a kind of affirmation that meaning and ambiguity must coexist.

More of his work may be appreciated on his website.

The works selected for this issue of The Pasticheur are courtesy of Marshall’s wife, Dianne (Dee) Arisman, and curated by Kristen Mattison, a previous contributor to this journal.

Portrait Credit: Dan Wagner

Curator’s Note:

Marshall Arisman’s art is never still. It moves between darkness and light, between what is seen and what stirs beneath. Though first known for his darker imagery, his work evolved toward a quiet reconciliation, an understanding that shadow and radiance are not opposites but necessary halves of the same truth.

The Angels/Demons series was born of a lesson from his grandmother, Louise “Muddy” Arisman, a spiritualist minister and psychic. When he was sixteen, she told him: “Learn to stand in the space between the angels and the demons. Do not try and join them”. In his studio, angels covered one wall, demons the other, and each day he stood between them, meditating on that space, on the balance between creation and chaos.

For Arisman, angels and demons were not moral absolutes but mirrors of one another. The angel, faceless and luminous, contains the seed of ruin; the demon, marked by shadow and gold, carries the pulse of divinity. Both embody what is human: the fragile symmetry of grace and desire, faith and doubt. The gold leaf that threads through these works seems less ornament than alchemy; the trace of transformation that unites their forms.

In his Ayahuasca series, Arisman extends this dialogue to the realm of origins. Inspired by the ancient cave drawings of Dordogne and the visionary rituals of South America, he painted a world where animal, human, and spirit overlap. The figures emerge from one another like memories returning to light. Rainbows, handprints, and layered silhouettes echo the first gestures of art: the desire to touch what cannot be named.

Across these series runs the conviction that every threshold is inhabited, that life and death, faith and terror, are intertwined states of being. Arisman’s paintings are not depictions but crossings: they invite the viewer to stand, as he did, in the open space between extremes.

What endures in his work is not doctrine but openness, a belief that illumination comes not from escaping darkness but from entering it fully. His angels, his demons, his animals and spirits, all inhabit that middle ground where contradiction becomes revelation. In their silent motion, we glimpse what Arisman most trusted: that the soul, in learning to bear its own weight, finds light even in shadow.