EDITORIAL October 2025

What Remains

To think is to lean on memory, even in its most fleeting forms. We recall a word, an image, a sensation already carried. Without memory there is no continuity of consciousness, no "before" against which the "now" can appear. Yet Borges, in Funes the Memorious, reminds us that "to think is to forget differences, to generalize, to abstract." Absolute memory is not thought but paralysis. Memory supplies the material; forgetting gives it shape. Thought is born where the two meet.

This imperfect balance is a gift. To hold everything would be unbearable. We sift through ashes and call the fragments memory. Walter Benjamin knew that history does not unfold in smooth continuity but in flashes, "images which blaze up at the instant when they can be recognized and are never seen again." And Giorgio Agamben adds that the remnant is not what remains after subtraction but what resists inclusion, what cannot be absorbed into the whole. Memory, history, testimony: each reveals itself not in completeness but in fracture, residue, insistence.

The works in this issue test these claims. Anselm Kiefer builds monumental canvases from rubble, ladders and axes broken yet transcendent. "Ruins, for me, are the beginning. With the debris, you can construct new ideas. They are the filters through which we see the past." Michael C. Roberts photographs the skeletal elegance of trees, stripped to essence yet stubbornly alive, the structure after the season has gone. John Grey turns us toward the body, a site of intimacy and survival, where "in bug world, we're sugar water, spilled crumbs, a faucet of blood and sweat and oxygen."

But Kimberly Grey, in her essay Mémoire, refuses the consolation. "Memory is not lodged or longing, but that it evades—and much as it wishes to animate the past, it is I who animates memory." Not Benjamin's flash but an act of will. Not the remnant that resists absorption but the self that refuses to let the past stay inert. Here the fragment does not insist. It waits, and we decide whether to touch it or let it go cold.

I stood once in a church ruin in Bremen, Germany. The walls stood but the roof was gone. Light came straight down into the nave. I thought I would feel loss. What I felt was exposure.

What remains is not still, and it is not always luminous. It flickers between ruin and radiance, yes, but also between presence and refusal. Some remnants offer themselves. Others turn away. The works gathered here do not preserve the past but ask what we are willing to carry forward and what we must set down.

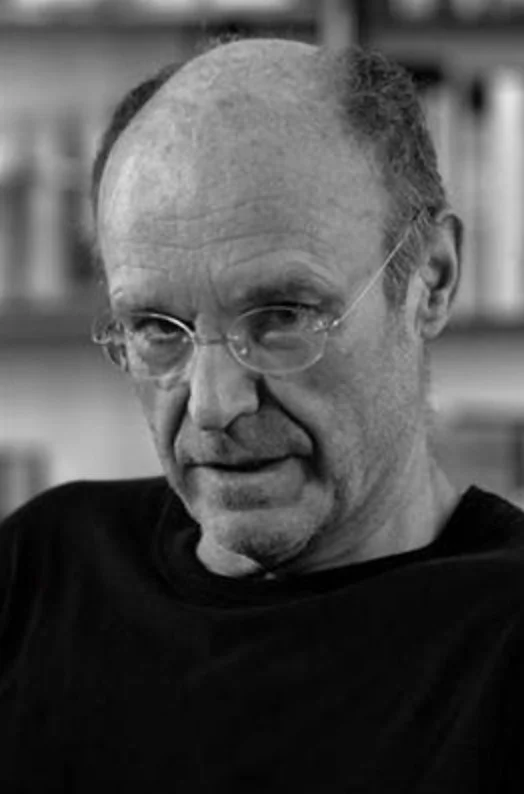

Jorge R. G. Sagastume

Editor-in-Chief

This Issue’s Contributors, in Alphabetical Order