EDITORIAL – July 2025

On Beauty, Burden, and the Unfinished Soul

"Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible." — Paul Klee¹

Art is not an answer but a disturbance. It does not seek to clarify but to complicate, to reveal not what is finished but what trembles in becoming. Paul Klee reminds us that art does not mirror what we see. It touches what resists being seen, what flickers at the edge of form, sense, or soul. This issue of The Pasticheur brings together work that remains open to change, that carries the burden of beauty like a wound, and that treats the soul not as a completed whole but as a question still unfolding.

In Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel suggests that art, philosophy, and religion are three expressions of a people’s absolute spirit. Art is not decoration but a kind of truth: the Idea made sensuous. But not all art carries this equally. For Hegel, Greek sculpture marked the height of classical beauty. After that, form became fractured, ironic, interior. The Idea, too vast now for simple form, pulled away from appearance and art turned inward.²

Nietzsche, in contrast, reminds us that the aesthetic is not a stage of spirit but a response to suffering. Faced with chaos, we make form. His vision of the Apollonian and the Dionysian does not demand balance but honors the dissonance between clarity and collapse. The greatest art, for Nietzsche, preserves the tension.³

So do the contributions gathered here. They resist closure. They deepen the rift between what we feel and what we can explain.

Richard Denner, also known as Jampa Dorje, moves from the cosmic to the domestic, from quantum speculation to filial care. Poised throws language into the void, where Buddhist logic meets vacuum soup. The Caregiver returns to Earth, tracing the incremental unraveling of an aging father’s mind and body. One work asks what we are made of. The other shows what is left when memory begins to slip away. Together, they form a diptych of the infinite and the intimate.

Miles Jordan’s 504–907 pairs photographs of New Orleans and Fairbanks. The landscapes are different, but the questions are shared: What holds a place together? What makes memory stick to walls, to streets, to skies? His diptychs, subtle and searching, suggest that contrast is a kind of kinship. That longing for one home often means carrying another inside it.

Pura López-Colomé listens rather than explains. Her poems do not describe. They receive. They let weather become prophecy, silence become structure. Each line is a pause, a flicker, a residue of time. She writes from the edge of perception, from where memory thins. What remains is not a message but a mood, unfinished, luminous, and unresolved.

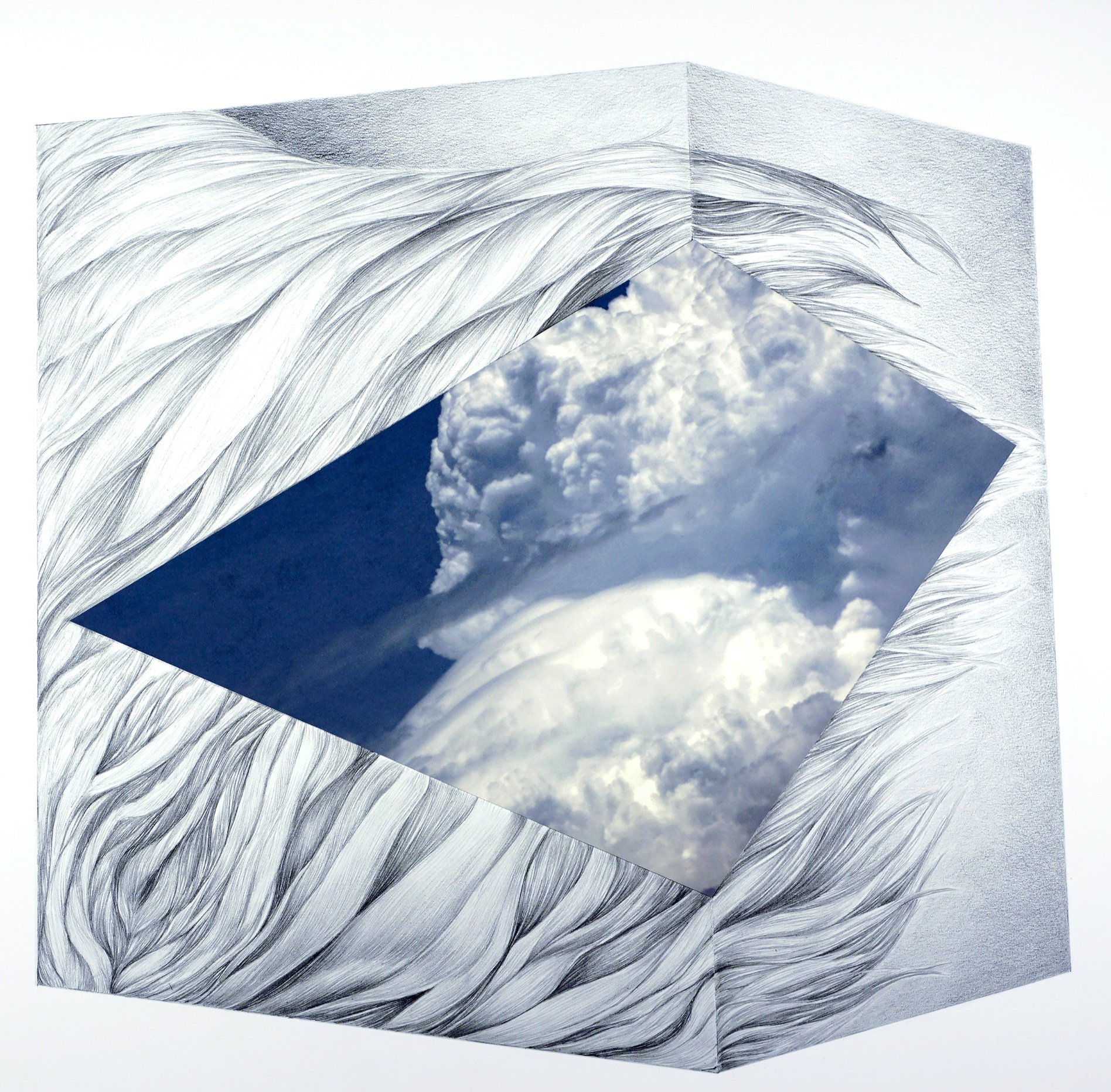

Jennifer Printz does not capture the sky. She translates it. Using textile and pigment, her pieces gather breath, light, and atmosphere into tactile experience. Her works are not representations but conditions, pleated, stitched, and suspended. They do not impose form on the sky but let its uncertainty settle into the body. Printz’s art is meditation made visible, a slow dwelling in what does not resolve.

Jane Sangerman constructs and corrodes. Her surfaces speak with rust, with residue, with the ghost of the urban. Layers of netting and fence collapse into lyrical ruin. Her pieces are visual elegies, gridded and grieving, tender with loss and vibrant with decay. The city does not just inspire them. It seeps into their material. These are thresholds rather than walls, portals where entropy and memory meet.

The soul of this issue is incomplete and should remain so. For Hegel, beauty gave sensuous shape to the Idea. For Nietzsche, it emerged from chaos, pressed just enough into form to help us survive it. And for Oscar Wilde, beauty was its own end, though he knew well that when pursued without measure, it could undo us.⁴ What this issue offers is not resolution but a set of rooms in which the not-yet can breathe. Each contributor leaves the door ajar, welcoming ambiguity, strangeness, and the sacred unfinished.

— Jorge R. G. Sagastume

¹ Paul Klee, Creative Credo, 1920

² G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on Aesthetics, trans. T. M. Knox (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975)

³ Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Douglas Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)

⁴ Oscar Wilde, Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891)

This Issue’s Contributors (in Alphabetical Order)