EDITORIAL

On ‘Who is the Enemy?’

Henri enlists in Napoleon’s army, and before going to war, his baby sister asks him: “[w]ill you kill people, Henri? I dropped down beside her.

- Not people, Louise, just the enemy.

- What is enemy?

- Someone who’s not on your side.” (The Passion, by Jeanette Winterson)

1. This comes from a piece of fiction, in part. 2. Wars continue to be waged for reasons like those of the time of Napoleon. And though words such as ‘enemy’ are disappearing from public speech and replaced with ‘those who are different’ or ‘those in disagreement’ the Napoleonic figure still rules. Changing attitudes that disseminate confrontation and, ultimately, hatred seems like an impossible task. Still, there are times when enough individuals agree on one thing and may oppose and expose the powerful, the modern-day Napoleon, causing some change, even when the latter loses only a battle and not the war.

Last month, for instance, students graduated from college, and, as is the tradition in the United States, there’s always a commencement speaker in the ceremony, who also receives, usually, an honorary degree conferred by the faculty of the institution as a sign of endorsement by the college or university. The speaker in my institution was set to be Michael Smerconish, a figure whose views on ethnicity are incongruent with those of some faculty members and students at several levels; twenty years ago and as recently as last month, he openly expressed his intense sentiments against Arabs. One of our Arab students wrote an article in the college newspaper voicing opposition to the choice made by the institution to have him as the commencement speaker. The basis for the disagreement was Smerconish’s racism and intolerance. The student engaged someone with whom she didn’t see eye to eye, and this caused the invited speaker to openly and publicly ridicule and shame the first-year Arab student writer. Most students and faculty respect differences in opinion; it is a basic principle and the foundation of freedom of expression. This is even encouraged in the classroom through dialogue by some of us. The same should be expected from an invited speaker.

Certainly, Smerconish is entitled to his opinions, and many, including myself, would welcome a dialogue with him that could lead to understanding important points of view. Yet, his public diatribe against the student writer constituted an act of intimidation, which was followed by death threats against Arab students and faculty in my institution, including a dear friend and colleague of Arab origin. Students’ response to Smerconish was strong and yet exemplarily peaceful. A handful of faculty members, organized by a leader, wrote a letter to the college’s president, asking to support students’ protests and their petition to replace Smerconish. I was the first to sign the letter; a small group of colleagues did the same. I signed not because I disagreed with him or was not on his side but because he placed the student, myself, and the opposing parties in the category of the enemy, not of the people. This was an action on his part, not an opinion. To me (to me), racism or any ism that leads to unethical decisions is not a difference of opinion, it is a move to suppress a group, members of a minority or not. Smerconish’s diatribe prevented other faculty members from going on the record for fear of negative consequences. I suspect many who didn’t sign shared the opinion of those who publicly did.

The college president withdrew Smerconish’s invitation to become the speaker, not because Smerconish thought differently (I think) but because of his actions. This led the disinvited speaker to create yet another public diatribe through his radio program and video, which millions saw.

Because difference is richness, the faculty had originally voted to confer the honorary degree upon the dismissed speaker despite his formidable and openly voiced sentiments against Arabs. Still, on our last faculty meeting of the academic year, a minority among the faculty who decided to participate voted to rescind the degree because intimidation cannot be endorsed.

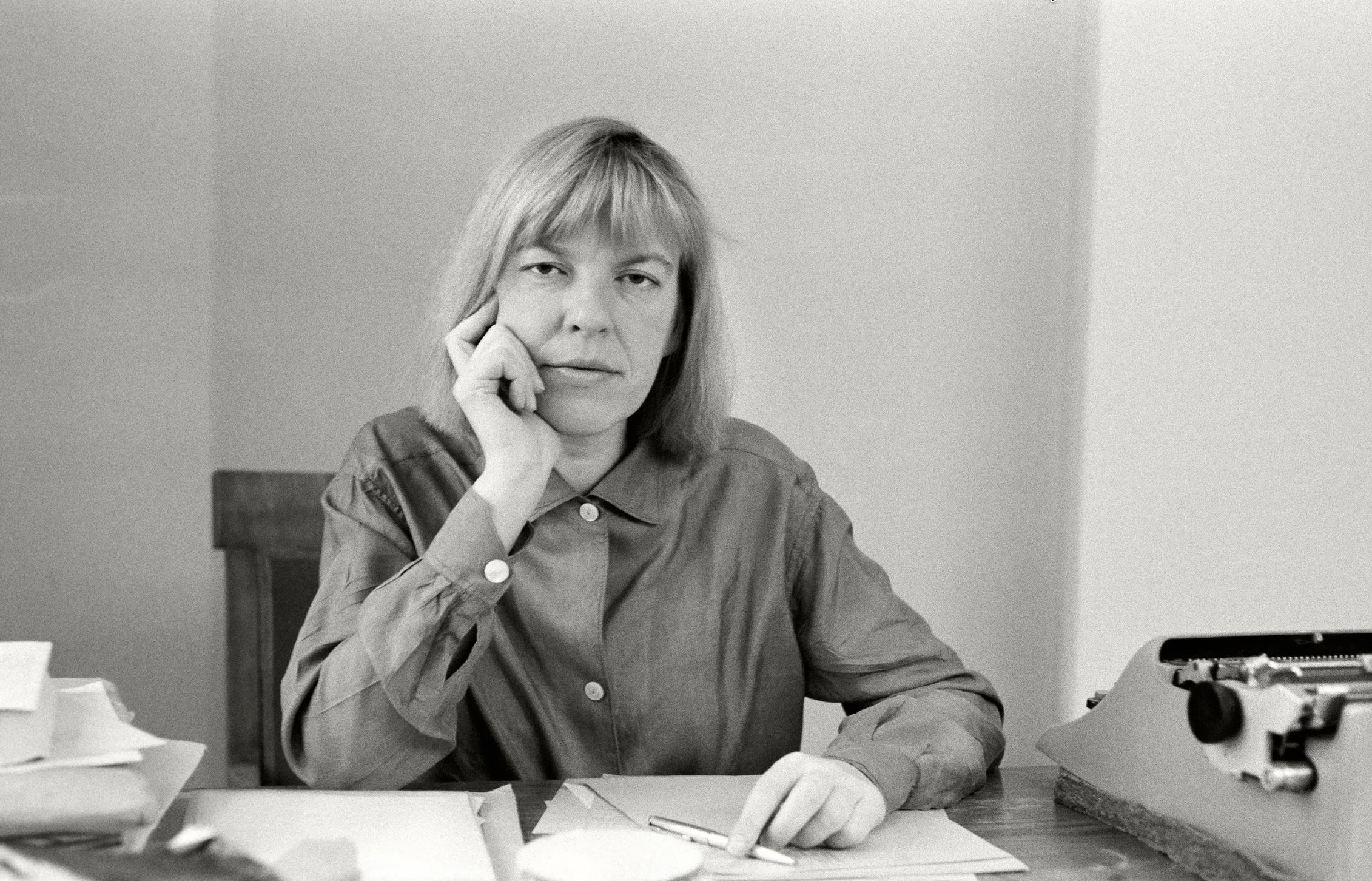

This is one of many incidents the world sees often nowadays, and it applies to all parties regardless of affiliation. One may play it safe against the powerful, who can and will intimidate. Some choose not to, openly or through art, literature, music, film, and other media. The roads leading to the present day have been corrected by thinkers who subvert harmful views, and this issue of The Pasticheur is dedicated to these individuals. Artists such as Curtis Talwst Santiago, who, through his work, denounces issues of migration and colonialism. Or Jordan Seaberry, whose ideas, activism, and art helped fight and pass multiple criminal justice reform milestones. Or the writer Ingeborg Bachmann, who challenged the establishment through literature and philosophy of language, along with Ilse Aichinger, Paul Celan, Heinrich Böll, Marcel Reich-Ranicki, and other members of the Gruppe 47.

I hope that publications like ours will help fight intimidation, discrimination, and racism. Our visitors need not agree with what we publish here, and opposing views are always welcome when they respect differences. As I’ve said, difference is richness: we will all be the same when we are six feet under the ground.

Jorge R. G. Sagastume, Editor

This Issue’s Artists