EDITORIAL

On the Ever-Present Now

Memory is a defect some of us come with from the manufacturer. Wouldn’t it be nice to be like Funes the Memorious, burdened by everything yet capable of recalling it all with perfect clarity? Or is it perhaps better to have no memory and always be in the here and now?

From a young age, I’ve been drawn to the metaphysical. I explored different religions, and my fascination eventually led me to literature and philosophy. This is how I stumbled upon Taoism and began reading the Tao Te Ching, a text that has since become a quiet companion in my reflections on life and art. Taoism, as it is known, explores principles like harmony, simplicity, and the art of living in alignment with the Tao—often translated as “the Way” or “the Path.” Rather than prescribing rigid doctrines, it presents an intuitive approach to life, one that values spontaneity, naturalness, and a kind of graceful acceptance of life’s rhythms and mysteries.

One of the most intriguing concepts in the Tao Te Ching is wú wéi (无为), often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action.” This idea doesn’t mean inaction; rather, it suggests a way of moving through life that aligns with circumstances instead of pushing against them or forcing outcomes. Laozi, or Lao-tse, often uses nature as a metaphor: just as water flows around obstacles without losing its essence or path, we, too, are encouraged to live with a similar fluidity, responding to life without undue resistance.

The Tao teaches that the present moment is the only true reality; the past is gone, and the future is unknown. In embracing the present, one finds a fuller, more authentic existence—unbound by memory’s weight or the anxieties of what is to come. This idea resonates with today’s emphasis on “mindfulness,” though Taoism understood it centuries ago. Yet, while we might not dwell on the past, each present moment we encounter accumulates, layering into the person we become and influencing how we approach life. Art and literature, to me, embody this ever-present “now.” They ask us to look, to read, and to experience them at least twice and to allow ourselves to be surprised by the obvious.

With this perspective, art becomes more than expression; it becomes a practice in acceptance, a way of finding inner peace through observation and participation. It is in this spirit that I present five artists, each with a distinct voice that explores and questions the purpose of art and literature within our shared human experience.

John Chang, a young Chinese artist, focuses on calligraphy. In China, calligraphy, or Shūfǎ (书法), transcends writing to become a spiritual and philosophical practice. Rooted in Taoist and Confucian traditions, it stresses harmony, balance, and self-discipline, demanding that one aligns their energy—or *qi* (气)—with a harmonious flow. The brushstrokes reflect the artist’s state of mind: balanced, calm, or strong. Mastering calligraphy is akin to mastering oneself. While I cannot say if this is John’s specific aim, I like to interpret it as such, believing that art, at its best, serves a purpose. Without purpose, it risks becoming merely an aesthetic exercise.

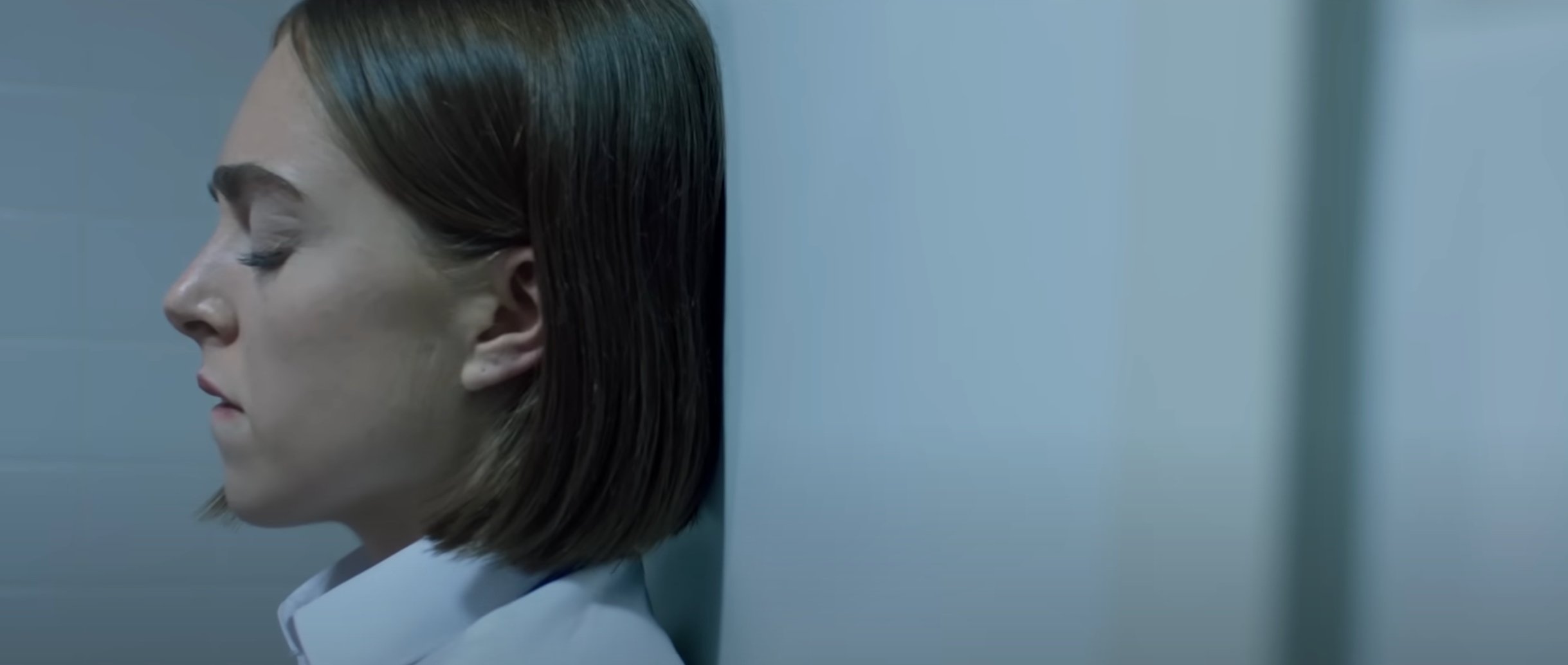

Turning to other forms of art—scriptwriting, directing, and acting—I am equally honored to feature Louisa Connolly-Burnham, an English filmmaker whose debut short film, The Call Centre, is included in this issue. Her work captures the complexities of life, motivation, and ethics, raising questions about choices that serve not just the self but the community. Louisa’s film reminds me that our decisions are inevitably shaped by the struggle to live fully in the present, to know how to act in the face of uncertainty.

The Indian poet Vandana Kumar also brings me back to the present, writing, “Seven years ago / Sits on my present / Like time sitting on the sting of a bee / On both sides of my exposed arms / In a sleeveless floral dress.” Her lines linger like an echo, a testament to how memory intertwines with the now. Meanwhile, Italian artist Stefano Questorio, with his experimental photography using expired Polaroid film, challenges our assumptions of what is “instant” and what is “expired.” His work pushes me to see these categories as arbitrary and incomplete.

Lastly, Alessandro Carrera—an Italian literary critic and poet—invites me to question the very notion of trust. In one of his poems, he writes, “I am your pilot. / You know, sometimes I don’t know who I am. / But you, who are you? Why are you here? / Where do you think you’re going? / What do you think you’re doing? / I am still your pilot.” His words resonate as a reminder that our words, thoughts, and actions inevitably shape those around us.

This editorial is not meant to influence our readers; rather, it is an invitation to reflect, to question, and perhaps to find a moment of stillness amidst the stories.

Jorge R. G. Sagastume, Editor

This Issue’s Artists