EDITORIAL

On the Modest and Secret Complexity

One of my favorite writers was fond of saying that all writers are baroque, vainly so, in the beginning. As the years go by, and if the stars are correctly aligned, they may achieve not simplicity because anyone can reach this, but a modest and secret complexity.

Fine art, fine art photography, and short filmography are not different from creative writing. They are another form of writing, another text, and to stand apart from others, as with writing, they need to have achieved this modest and secret complexity.

But why does it have to be secret? It is interesting that the word ‘complexity’ is intimately related to another, complicity, that nowadays seems to connote an element of negativity, just as secret does. Yet, I would like to briefly discuss this relationship to show how complexity in art must lead unavoidably to complicity. The first word comes from the Latin complexus, the joining of the prefix com- meaning ‘all together’ and plexus, fold, intertwined; the latter comes from Middle English complice, from Old French, which is also derived from the Latin complexus. Suppose that both words complexity and complicity are accomplices. Then, it makes sense that a work of art needs to become an accomplice with its audience; without this complicity, the work is insipid. And I emphasize that this complicity must exist between the recipient and the work, not its maker.

It gives me pleasure to introduce the work of seven outstanding artists. Some are well-known, and we hope that others will become so because their work stands apart.

Conrad Egyir’s works are strong metaphors drawing from Western culture and philosophy. In recent years, his paintings were discovered by Disney and Conrad’s work began to be read with different eyes. We present some of his paintings and drawings here, wishing our readers to establish their own complicity with the work, uninfluenced by the discourse created by the experts and the media.

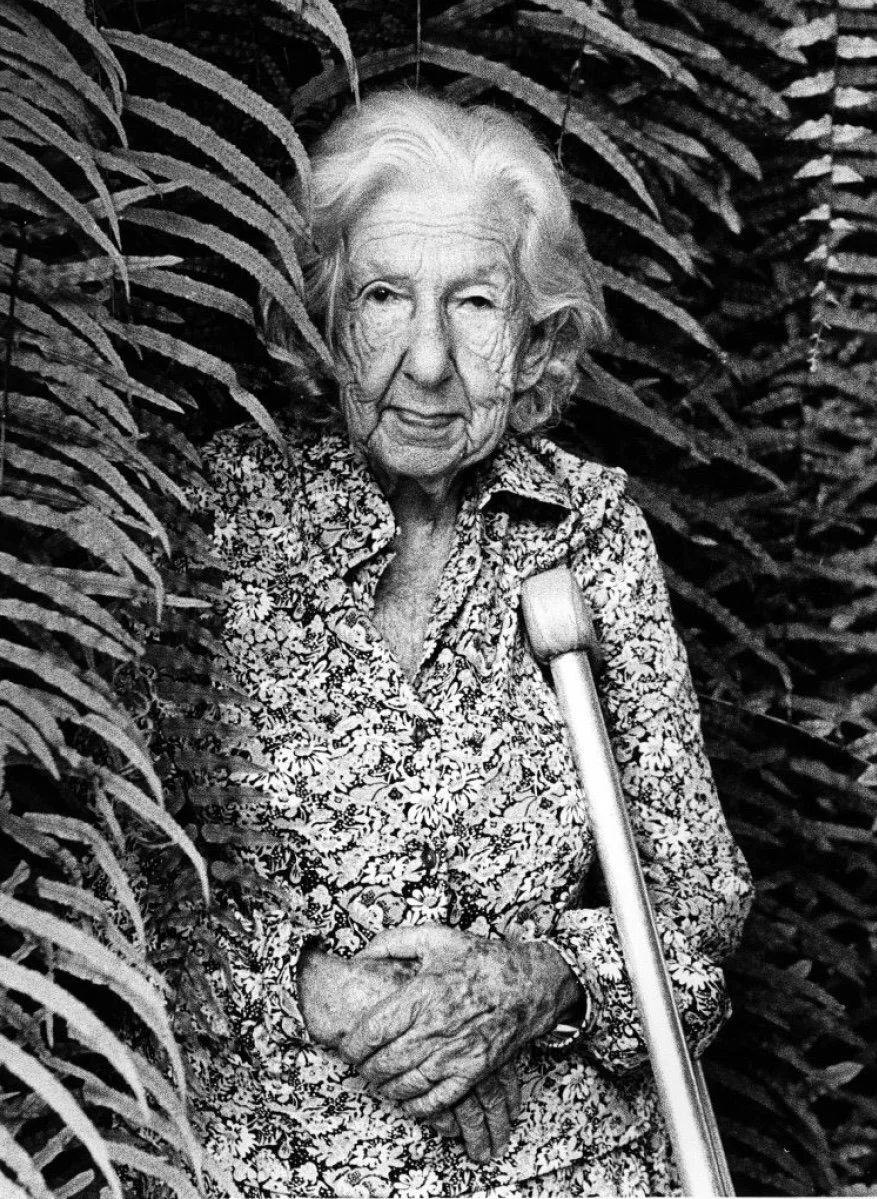

Cora Coralina‘s writings probably will not shadowed by others’ opinions because her work is not very well known in English. Yet, in her mother tongue, Portuguese, is as known as her contemporaries, the Argentine Alfonsina Storni or the Uruguayan Gabriela Mistral. I’m hopeful that English readers will discover her powerful, and deceivingly simple, poetry, so that “[we can] put together all the stones that have come down on [us]” and build with them something useful for humanity.

Jana Lulovska’s work can’t be introduced in a brief paragraph. This Macedonian artist is a master of interdisciplinarity who transforms different media coherently, producing unique cultural artifacts, from pictorialism to painting, photography, and film that become strong metaphors of reality, touching on the female and human experience.

In a similar way, the subjects of the French-Swiss photographer Émilie Möri are mainly women, focusing on female ataraxia, dreams, and timelessness. Émilie’s work effectively immerses the viewer in a sea of calmness and reflection. Her images are far from simple, and the way the artist chooses color, light, props, and postures has an effect that I (I) can only call naïvely ‘magical’.

Human nature turns into torment with the feature short by Aline Magrez, a young filmmaker and director from Brussels. I came across Aline’s work over a year ago, while searching for short films that I could use in a creative writing class to teach students the inner works of fiction writing; she happily agreed to allow me to use three of her films to do so. The short that we feature in this issue of The Pasticheur, is her graduation project. I trust the viewer, like me, will discover how Aline’s film connects with the audience and makes it an accomplice.

This complicity becomes evident as well through the photographic work of Anna Weidle, originally from the Republic of Moldova. Her work is candid and unapologetic. Her images are characterized by honesty, touching on topics such as menopause and depression, while blurring the differences between the sexes.

And, the new poetry of Sofia Getoff-Scanlon approaches different topics, with an underlying exploration of the self, reminding me that all ages and stages of life are nothing but individual gifts that I must take, yet always looking at things at least twice, after all “[e]ven a predator is beautiful until she goes for the throat”.

I hope the readers of this issue will take the time to immerse themselves in the worlds portrayed in the works of these artists and writers and allow themselves to be surprised by the obvious.

Jorge R. G. Sagastume, Editor

This Issue’s Artists